I feel languorous and elegant. I raise my arms above my head and arch my back, shaking the sleep off my shoulders. The morning light filters through the closed wooden blinds, and the deep yellow walls of our bedroom glow like a Tuscan landscape.

I gauge my mood by thinking of all the things I have to accomplish today. Nicole needs a new pair of jeans. I promised Mamita I would take her to the grocery store. I also have a paper to work on for school, or not. Do I feel the oppressive weight of responsibility on my chest? I spread my toes under the sheets to test the waters.

Nope. It seems I will be Anna la Buena today.

I spread my hands against the paisley-patterned comforter. The framed images of my children smile at me on their perch on the dresser. The book Felix tossed on the floor awaits its recovery from ignominy back to the nightstand.

Last night’s twin acts of cathartic release in words and flesh allow me to turn to a fresh page. Like Scheherazade, I live to see another day and tell another tale.

But where do stories come from? There must be a primal source where tales are gestated between the furrows of a fertile imagination. It is a land of milk and honey and tears where words slowly unfurl like rare flowers, creeping up from the dirt, their roots reaching to the center of the earth and the beginning of time. It is an Eden that all storytellers long to return to as they…as we must learn to plant our seeds in exile.

Did God really think we’d be satisfied with giving the animals, plants, and minerals their names? Or with chronicling the minutiae of our allotted hours under the sun? Did he hope we’d just stick to singing his praises? One bite of the crisp apple allowed us to create worlds within worlds, tempted by the ripe, forbidden language of our original sin. And can the sins of the father visited on the daughter be rewritten in space if not time?

I look at Felix, who’s still sleeping. Kitty Kitty, a stowaway under our bed last night, is curled up by Felix’s feet.

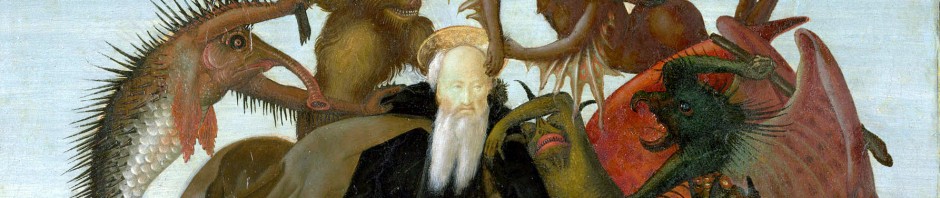

I’ve created an empirical empire around the edges of Felix’s body. As long as I can see him, I can touch him. He is the parted lips, the fluid arms, the smooth chest that lie undeniably next to me. My eyes see more truth than my mouth could ever utter. I behold an angel. A burning seraphim. Isaiah’s winged serpent. He understands and does not judge. Holy, holy, holy.

Like me, Felix is an only child. He is not close to his parents who were adequately attentive but did not make him the center of their universe, like mine did. This is mainly because his father has been for most of Felix’s life a melodramatic alcoholic who demands the lion’s share of Felix’s mother’s attention, leaving little for Felix.

In response to the paucity of emotional indulgences he received as a child, Felix learned to be focused, efficient, and has steered clear of drama. He has always known what he wanted, and somehow this includes me, a drama queen if ever there was one, but also generous, if overwrought. But lest this seem a paradox, Felix by no means married his father nor is he reenacting his mother’s long suffering. He wouldn’t put up with my bullshit if he felt our children would suffer. I respect this and have never crossed that invisible, immovable boundary.

“Felix?”

“Wha?” He says with his eyes still closed.

“You are my sun and my moon.” I plant a kiss on his cheek.

He puckers his lips and continues sleeping.

§§§

“Can you believe what’s happening in Rwanda?” Felix points to the paper. “I know you don’t want to hear about it. But this is insane.”

I wince. “It’s not insane. It’s evil.” I sip my coffee and vow to stick to the local section of the paper.

“How can you kill a child in his mother’s arms?” Felix puts the paper down and wipes at his eyes.

“We’re all capable of evil, Felix. That’s the scary part.” I don’t look at him.

“Everything OK?” He’s reading my face as he holds his hand out to me.

“I’m OK. Really.” I take his hand.

“Really, really?” He proffers a piece of crisp bacon.

Daniel (who’s really a bug tester off to collect samples in the wild) runs by us in a dragonfly blur of nets and strings and flings open the French door to the backyard.

“Really, really, really.” I bite the bacon in half and poke him on the arm. “Tag, you’re on backyard adventure duty.”

§§§

This mango didn’t fall far from the tree. I am the product of a subtropical Cold War childhood shaped by the critical mass of parents and grandparents orbiting around me. I had way too many doting adults feeding my bottomless need for attention.

I was especially pampered (and still am) by Mamita, who sewed my dresses, made my bed, tamed my locks, gave me a dollar every day for the ice-cream truck, and never asked me for the change back.

My Saturday mornings were presided over by los viejos, Mamita’s brother and sister, who, like all good Cuban exiles, savored conspiracy theory politics over steaming saffron rice and sticky, garlicky chicken. Huddled on the orange lounger in the Florida room watching The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Hour, I’d keep getting up to raise the TV’s volume as their voices grew louder in spirited disagreement over who was a hated communist and who was just a plain idiot.

It was so simple when I was kid—if I woke up late and the only kids’ shows left on TV were Fat Albert and the CBS Children’s Film Festival featuring the disturbing puppet act of Kukla, Fran, and Ollie, then the day was going to be as dreary as a Czech movie about an orphan and an abandoned puppy lost behind the Iron Curtain.

But if I turned the TV on and heard the opening strains of “Overture, Curtain, Lights,” oh joy—I had one glorious hour, including a barrage cereal and toy commercials, to watch Bugs Bunny while wearing my pajamas and eating potato chips and soda for breakfast. Back then I loved Bugs because he was such a wise guy. Now I revere him as a demigod of justice because he’s a wise guy and a pacifist at heart—he’s all live and let live until he’s pushed too far, and then, of course, it means war.

And like the gags in my favorite Looney Tunes, I’ve learned that time is circular, like the orbit of heavenly spheres and the pull of the nucleus as well as the sun. It’s a serpent eating its tail, the ouroboros, as history repeats itself, if not in the precise details, then at least in the punch lines. Elmer Fudd blows off Daffy Duck’s bill with a shotgun again and again and again. I always laugh.

My parents were a splendid couple who played Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, and the Easter Bunny with great alacrity. They celebrated my birthday with fancy cakes and imported oversized piñatas of animals like a fox, a tiger, and a burro that were as big as me. My parents invited their co-workers whose children stared back at me years later, spectral-faced and nameless in fading photographs. Had they enjoyed my party? I guess I hadn’t cared as long as I got presents.

Our yearly vacations were financed by my parents’ Republican, two-income, white-collared credo and an almighty American Express card: that stern, helmeted profile printed on plastic was as familiar to me as Barry Goldwater or Walter Cronkite.

I grew up on catchy jingles that pedaled cigarettes and detergent with the same manic enthusiasm. This was a golden age of consumption. Happiness depended on rows upon rows of products on store shelves. Tune into any of the three networks, and Americans were in love with talking horses, witchy housewives, and favorite Martians. War, poverty, racial tensions, and the threat of nuclear annihilation were limited to half-hour time slots on the evening news.

My father was a walking American Dream statistic: young Cuban immigrant starts over in a new country, learns the language, changes his name from Jesús to Jay, climbs the corporate ladder to suburban affluence, takes up golf, has a mid-life crisis, buys a sailboat, hears the sirens, and sails off the edge of the world. God bless America.

There have been certain cataclysmic eruptions that sporadically infuse our lives with a fresh breath of chaos, making possible new equations hitherto unknown or unimagined. Thus the pivotal events that led to my birth—from the first division of a single cell, to the crucifixion of Christ, to the Cuban New Year coup d’état of 1959—all have contrived to place me in the Burdines children’s department fitting rooms while my daughter tries on jeans.

Nicole pouts her lips at her reflection in the mirror, her hands on pre-puberty hips, visions of MTV vixens dancing in her nine-year-old head. In the harsh lighting and neutral tones of the fitting room, I try to see beyond the first three fleshy dimensions to the fourth, time, which can only be measured in the aging and the changing and the distancing of the first three. Nicki the girl will one day become Nicole the woman, and not, if I have any say in it, Madonna the pop slut.

As each generation spreads its wings, it leaves behind a carefully constructed nest of illusions built by previous generations. Without meaning to, I have become my parents, reaffirming a sort of materialistic covenant handed down from mother to daughter and father to son. I can trace my complicity in my own children’s excess of new toys under the Christmas tree, birthday fanfares, and lost teeth snatched from under pillows in exchange for a new dollar bill.

I remember my father’s homecomings after business trips and my anticipation, never disappointed, of a new doll for my collection tucked into his suitcase. He never failed me – at least not in a consumer sense. Later, his bags unpacked, his dreams undreamt, his dissipation and disillusionment complete, he lost his taste for material pleasures and plunged into a joyless ocean at the center of his mind.

I guess there are things that are best not handed down from generation to generation. My deepest fear is for my children to grow up in the shadow of the Beast.

“Mom? Are you listening?” Nicki is tugging a lemon yellow T-shirt over her head.

“Uh-huh.” I check the price tag and let her proceed.

“So how does it end?” Her head pops out of the collar.

“What?” Now I’m confused.

“The two Marias?” She pulls on a pair of black jeans.

“Oh. Well, what do you think happened?”

Nicole swings her hips back and forth, assessing her rear end in the three mirrors that line the dressing room and responds without looking at me.

“I think the first Maria that the Prince sees is the good one, and they fall in love. The bad Maria gets jealous and tries to trick the Prince. But when he kisses her, all that gross stuff comes out of her mouth, and he cuts her head off. The Prince and the good Maria get married and live happily ever after. The end.” Nicki shimmies off the black jeans.

“Not bad, but you forgot one thing. The Prince’s horse the color of wet dark brown hair falls in love with Maria la Buena’s horse, who is, before you ask, black with a white star on her forehead. Then they all get married, have beautiful children and ponies, and live happily ever after. The end.”

Nicki suppresses a smile as she zips up a pair of khaki pants.

“You look beautiful, Nicki. Why don’t you get both the blue jeans and the khakis?” I say.

“And the black jeans, too? Please?” Batting her lashes in triplicate reflections, she is shameless.

Will denying her instill some moral fiber in the midst of the degenerating forces of indiscriminate consumerism? Should I summon the crushing, but economically correct “We can’t afford it” leviathan? Heaven knows my parents never stooped so low, always serving up both the surf and the turf so that I wouldn’t have to make a choice.

And who says I want to grow up to be like my parents?

But Nicole looks so lovely with that first flush of feminine awareness, reminding me of my own past hierarchy of needs, when I would rather have been hit by a truck than not get asked to a dance.

On the other hand, Nicole is only nine years old.

Perhaps the universe is expanding and time accelerating, not in measurable minutes and seconds, but in invisible sub-particles that hurl themselves through space with sufficient velocity to turn a child into almost a woman in the span of nine years.

Suddenly I feel wiser and magnanimous. Let Nicole be a kid; she’ll turn into an adult soon enough.

“Mom, can I?”

“OK, baby.”

“Can I wear the blue jeans home?” She places a coy finger between her teeth, a budding Lolita with all the freshness of a brand new car leaving the showroom, not a scratch on her.

I nod. Now all I need to decide is how to pay for this indulgence: Visa? MasterCard?

American Express.

“And, Mom?” Nicki gathers the clothes in her arms. “Ponies aren’t baby horses. Ponies are just small horses.”

Well. Good thing God didn’t answer my prayers for one because that’s not what I wanted.

§§§

I help Mamita push the cart down the canned goods aisle. Her silver head reaches to my shoulder. We walk, stopping every few feet.

“Can you get that can of garbanzos for me up there?” Mamita points to the top shelf.

“Just one?” I reach for a can.

“Get me four. I don’t know when you can bring me back again.”

I place the cans in the cart, and we continue walking.

“Have you ever tried this?” I hand her a package of seasoned rice.

“No, is it good? You’ll have to show me how to make it.”

“Sure.”

Mamita puts the package in the cart and starts walking, then stops again. She reaches in her purse for her glasses, and her grocery list falls to the floor, coming to rest by her baggy ankles. I bend down to pick it up for her, and I can smell her. It is a smell like talcum powder and old clothes. I hand the list back to her, and Mamita puts her glasses on, holding the list up to them.

“What does that say?” She points to a scratchy word in pencil.

“Evaporated milk.”

“Oh, we already passed by there.” She keeps staring at the list which shakes a little in her spotted hands.

“That’s OK. I’ll go back and get it. You keep walking.”

I bolt across two aisles and stare up and down at the towering rows of milk products: I have to pick up Nicole from Jenny’s house, pick up the dry cleaners, renew overdue books at the library, water plants. What am I looking for? Oh yeah, where’s the evaporated milk? Shit, I forgot to ask her how many cans? Shit, shit. I forgot to defrost the steaks for dinner. I pace trying to locate the right brand of milk.

There’s a tug at my sleeve, and I jump around.

“Mamita, what are you doing?”

“I forgot to tell you how many cans I need.” She points to the quaint little cans with the cow on the white label that are right in front of me.

“I think six will do.” She looks up from her list, peering over the top of her glasses, and smiles at me. I put the six cans in the cart, and we start walking again.

At the checkout counter, she remembers she needs denture cleaner.

“I’ll get it.” I squeeze by a lady who’s pulled her cart behind ours.

I return with three different brands.

“That’s the one on sale.” My eyes bulge, and Mamita selects one.

The cashier grabs the chosen box from Mamita and shoves it across the scanner. I turn around to smile at the lady behind us line, and she turns her back on me as she browses a National Enquire.

“That’s $68.19,” the cashier says.

Mamita takes out her red leather coin purse and opens it. The bills are neatly folded, and she counts her money, one bill at a time. I help the bag boy with the groceries. On the way to the car, Mamita holds onto my arm.

“I can’t stand the heat.” She takes out a flowered cotton handkerchief.

Mamita lived in Cuba until the age of fifteen, when in 1926 she moved to Ybor City, Florida. But she’s never had a suntan, or a paying job, or driven a car, and she’s never been alone or unnecessary.

I open the car trunk for the bag boy and walk around the side to open the door for Mamita. I help her in and put her seat belt on for her. The bag boy slams the trunk closed.

“Thanks.” I hand him two rolled-up singles Mamita slipped to me and then get inside the car, start the engine and put on the air conditioner at full strength.

“That feels good.” Mamita wipes her face and neck with the handkerchief.

“Mamita, how did the story of Maria la Buena and Maria La Mala end?”

She looks like she’s about to answer and then frowns. “I can’t remember.” She seems flustered by this lapse in memory. She takes out a peppermint candy from her purse, unwraps it, and pops it into her mouth.

“Do you want a candy?” She takes another piece out of her purse.”

I shake my head and start to pull out of the parking space.

“Do you think you could take me to the pharmacy?” Mamita asks. “It would only take a minute.”

I stop and put my head back on the seat and close my eyes.

Money for the ice cream man, the smell of lavender soap, thinly sliced ham on Cuban crackers, the soft folds under her chin, party dresses, crying on her lap, warm milk, paper dolls, stories with witches and evil twins, sandwiches wrapped in aluminum foil with the dull side up, steaming white rice, short ragged nails, Band-Aids, the whir of the sewing machine, and the smell of bleach. I open my eyes.

“Of course.”

As we pull out into the afternoon traffic, I put my hand on her lap.

“I know,” Mamita says as she puts her hand on mine, “I know.”

§§§

After taking Mamita to the pharmacy, going through the Burger King drive-through to pick up a Whopper Jr. and fries for my grandfather, Papito, and leafing through three separate mail order catalogues proffered by my Mom to select a bathing suit for Mother’s Day, Nicole and I are almost home when she reminds me about the birthday party she has tomorrow, and we head back to the mall to pick up a gift.

I’m exhausted by the assault of familial obligations today. I’ve spent the whole day in careful observation of others’ needs, obliging, and even necessary, but I’m dying to disgorge my head.

I cut my mother off at the fourth fashion catalogue, begging the urgency to go home to make dinner.

“Annie, you’re always in a hurry.” My mother says this without anger or reproach. “I know you have so much going on, but I’d love more time with you when you’re not running around.”

Ouch. To obliging and necessary, add guilty.

Now as I speed up the entrance ramp to the expressway, I consider my relative merits as a daughter, granddaughter, wife, mother, and I find myself wanting. Not in specific acts and gestures, but in spirit. I have caught myself in the act of going through the motions of being a good person.

“Mom, what are you thinking?” Nicki’s voice in the dark startles me.

“Melvin Spleen.” My mind has taken a quantum leap.

“Who’s he?” Nicole looks out the window. I think there’s a strand of hair in her mouth, but I can’t tell for sure.

“This man I once met. He was old and probably poor, but his black skin and white hair looked clean and his clothes were well cared for. He was always at the street corner near my work. This was before you were born. He’d just stand there, leaning on a slim metal cane, and if you looked him in the eye as you passed by, he’d put out his hand, palm up and say ‘God bless you, child,’ with a short nod of his head.

“Most people just kept walking. But two things about him struck me: one was his neatness and the other thing was his age, for he was wrinkled like an old wise man. I wondered how he’d ended up a beggar. I thought of Papito, but if Mr. Spleen had any children or grandchildren, he’d been abandoned by them.”

I keep to the right lane on the expressway to let faster traffic pass me on the left.

“Did he live under a bridge like those people by Daddy’s work?”

“He wasn’t like that. He had an amazing grace. The first time he asked me for money, I gave him some change, and he smiled at me and said, ‘God bless you, child.’”

“That was nice. He was probably hungry. Did other people give him money?”

“Sometimes. But one time I didn’t have any, and when he held out his hand, I told him I was sorry. And you know what he said?”

Nicole shakes her head.

“‘God bless you, child.’”

“What a nice old man.”

“I got cash out of the ATM and got change when I bought lunch. When I saw Mr. Spleen again, I held out a dollar for him. Know what he said?”

“Thank you?”

“‘God bless you, child.’”

Nicole slaps her forehead: “Again?”

“That’s what he always said. One day I could see him from a distance, standing by a phone booth at the corner, so I pulled out a dollar for him. When I gave it to him, you know what he said?”

“God-bless-you-child.” Nicole nods her head stiffly from side to side saying each word like a robot.

“Nope. He gave me a business card and said ‘You dial this number for me.’ The card was plain white with black lettering that said ‘Confidential Palm and Tarot Readings. Call Krystal.’ And it had a phone number.”

“What does that mean?”

“It meant that this person, Krystal, could look at your hands or a special deck of cards, and she could tell you about your future, what was going to happen to you before it happened. Mr. Spleen handed me a quarter from his pocket.

“‘You call this number for me. Tell Krystal that Melvin Spleen, that’s me, wants her to pick him up. Tell her where I am.’ It was the most words I’d ever heard him say. He had a soft Caribbean accent.”

“What’s a Caribbean accent?”

“You know, like Sebastian in The Little Mermaid. We walked over to the phone booth, and I dialed the number. It rang about five times before a young-sounding woman, also with a Caribbean accent, answered ‘Your call was foretold.’ So I said ‘May I speak with Krystal?’

“She said ‘Speaking. Who is this?’”

“I thought she could see the future?” Nicki asks.

“Maybe I caught her by surprise. I told her I was calling for Melvin Spleen, that he was at the intersection of Flagler Street and Miami Avenue, and he wanted to be picked up. And she said ‘You tell that good for nothing grandfather of mine that I’m busy now. Tell him I ain’t got no time for his lazy, drinking ass. Tell him I’m working. Go on, you tell him.’ I could hear a man laughing in the background. Then she hung up.”

“Maybe the old man wasn’t such a good person. What did you tell him?” Nicki’s eyes screw up in the corners as she waits for me to pass judgment on the seemingly not-so-nice Mr. Spleen.

“I told him Krystal couldn’t come now, that she was with a client. I handed back her card, so clean and white, and gave him another dollar. He said ‘God bless you, child.’”

“I know, I know. Then what happened?”

“I left him stranded at the crossroads. I felt awful for Mr. Spleen, even if he wasn’t such a nice old man. So on my way home that day, I stopped and bought Papito a pound of his favorite chocolate-covered peanuts and a couple of cigars.”

I watch through my side-view mirror as a black jeep approaches on the left and speeds by, swerving a little into our lane. Someone on the passenger side has his bare leg hitched up on the door panel with his foot out the window; he spreads and waves his toes in greeting as the car speeds by us.

Take me with you.

“But I thought it’s bad for Papito to smoke?”

“Yes, and it’s bad for Mr. Spleen to drink. But I still gave him a dollar whenever I saw him.”

“Why?”

The jeep’s taillights diminish as the ever-expanding horizon outpaces my ever-contracting universe. Glancing in the rearview mirror, I just make out the dark hump of the Beast’s silhouette in the backseat. Objects in mirror are closer than they appear.

“Because, Nicki, we have all made our choices.”